This article has been summarised at Urban Cinefile. I am uploading it here, importing from our old website, because it has some still-useful insights from still-expert experts.

The clue was on the flyer: a picture of the hairless Sphynx, one of the world’s jarringly un-fluffiest of cats. At the 2012 AFTRS seminar, “Not Fluffy: Reimagining the Creative Enterprise,” six of Australia’s leading researchers in screen business each tried to answer the question: are screen practitioners fluffy-minded artists? Or are they like the Sphinx – tough-minded creatures, with little more than their keen nose for a business opportunity to protect them from the ravages of a competitive industry?

This article has been summarised at Urban Cinefile. I am uploading it here, importing from our old website, because it has some still-useful insights from still-expert experts.

The clue was on the flyer: a picture of the hairless Sphynx, one of the world’s jarringly un-fluffiest of cats. At the 2012 AFTRS seminar, “Not Fluffy: Reimagining the Creative Enterprise,” six of Australia’s leading researchers in screen business each tried to answer the question: are screen practitioners fluffy-minded artists? Or are they like the Sphinx – tough-minded creatures, with little more than their keen nose for a business opportunity to protect them from the ravages of a competitive industry?

David Court: The King’s Men – Five great lessons from William Shakespeare’s theatre company

David Court, the Head of the Centre for Screen Business at the AFTRS, explained to the gathering of 30 screen producers and practitioners that even the great artists like Shakespeare are not as fluffy as everyone might think.

According to David, William Shakespeare’s theatre company, 10% owned by the Bard himself, was run in a most pragmatic fashion. The Bard’s first company, “The Lord Chamberlain’s Men,” faced a steep rent increase. At that point, pragmatic Shakespeare brought in a gang of “strong men” who pulled the theatre apart, from pillar to post, then re-assembled the theatre across the river. The newly assembled theatre was renamed “The Globe.”

Shakespeare then tapped into what we would now call “market segmentation.” He established a new theatre within the exclusive, and expensive, precinct of The City of London. The Globe charged only 1 penny for admission, whilst the newly built Blackfriar’s Theatre, with its smaller capacity, charged a steeper entry price of sixpence. By setting up in a more expensive location and charging a higher entrance price, Shakespeare and his theatre company, now called “The King’s Men”, took what was then an art form for the masses into “high art”, for an elite and wealthy audience. Think Woolworths, selling apples for $2.98 a kg, and its high-end store, 50 metres away, selling them for $5.98 per shiny punnet.

David dispels the myth of the artist as “a lonely man (and then, it was typically a man), sweating away at his art in a dusty garret.” He blames this common, but misguided belief, on Romantic era thinkers such as Lord Byron, and later repeated by non-artists such as John Maynard Keynes in his acceptance speech for the position of Director of the British Arts Council.

David suggests that at least Shakespeare clearly did not conform to this stereotype. Shakespeare worked closely with his troupe of actors, borrowing liberally from other creative sources, and repurposing old material. This was a great artist, and one actively engaged with realizing his art in a practical, and responsive business-like fashion.

David draws out five business lessons for screen practitioners from Shakespeare’s story:

- Build common purpose companies. David sees Matchbox Pictures, Cordell-Jigsaw and Zapudra’s Other Films (Andrew Denton’s production company) as local examples of this.

- Negotiate terms of trade. Clearly, The King’s Men were not passive in accepting the terms dealt them, but David sees too many filmmakers prepared to accept less than profitable deals “just to see their films released.”

- The Audience is the Asset

- Build the Brand

- Embrace the Business

Box Office Prophecy, presented by Dr Jordi MacKenzie

Dr Jordi MacKenzie of Sydney University is trying to bring some predictability and measurability to estimates of likely box office takings of a yet-to-be-released feature film. The boldness of this experiment flies in the face of conventional wisdom that says box office earnings of a film are too unpredictable to allow meaningful forecasts.

The study, now in its 5th year has managed to strip back the information required to make accurate predictions about box office to nothing more than the key cast and crew list. Good results have also been obtained with only a small number of screen industry participants, sometimes as few as 10 in each “game”.

The researchers have found a correlation of r = 0.95 between actual box office results and their predictions. In statistics-land, this is very, very robust. A correlation of ‘1’ is a perfect correlation, with ‘0’ being no correlation – and a correlation like what Jordi and his co-researchers obtained is virtually unheard of in natural phenomena.

The question researchers asked participants was not “What do you think [film X] will make at the box office?”, but “What do you think others will think this film makes at the box office?” This was a conscious attempt to divine the “Wisdom of the Crowd” phenomenon. In academic-speak they call it a “pari-mutuel” technique.

Another benefit of the study in using this technique is that they were able to have the predictions naturally render themselves into probability distributions, rather than a single point prediction. This enabled the researchers to then quantify the uncertainty surrounding each prediction.

Whilst his statistical figures were too small for me to scrutinize from my vantage point, Jordi is confident that the research team has found a methodology that could be extremely useful in guiding early investment and financing decisions of individual film projects.

For those who are curious, the research paper is available online for free and entitled: “Nobody knows anything? Applying pari-mutuel information aggregation mechanisms to the motion picture industry.”

Copyrighting the Future, presented by Professor Michael Fraser

Professor Michael Fraser of the University of Technology Sydney next took the lectern and argued quietly but forcefully for a copyright registration database, which he dubbed the “National Content Network” (NCN).

The professor is realistic about the environment that faces IP enforcement, acknowledging that enforcement causes alienation within society. This is because digital film piracy is practiced by 1 in 3 of the population. Consequently, in his words, “enforcement alone won’t fix this market failure.”

Michael proposes a solution, simply stated: “Creators have to offer a better service.” His National Content Network would give both consumers and creators what they want. Creators want to be paid for their IP. But what do consumers want? According to Michael, they will pay for:

- Instant access

- Freedom to repurpose the material (“mash-up”)

- All of this in one transaction

Of copyright’s importance, Michael says that a fair and enforceable copyright law was the essential ingredient to the Industrial Revolution. He noted Imperial China had copyright law well before Europeans, however, it gave all copyright to the Emperor. British law dating from the late 17th century on the other hand specifically protected a citizen’s intellectual property (IP). It was this difference, he feels, that allowed the West to surpass China in technological terms, and how it came to dominate the World.

To further support his argument, he referred to Article 27 of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights to the effect that “If you can’t make a living from your work, you are silenced.”

Creative Futures – presented by Tony Shannon

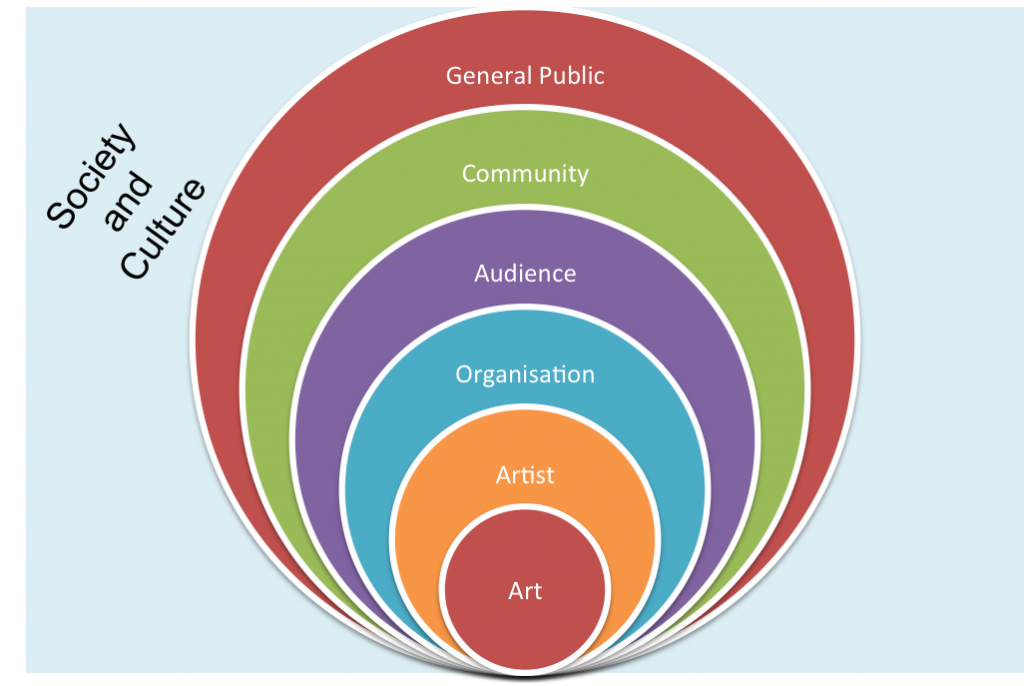

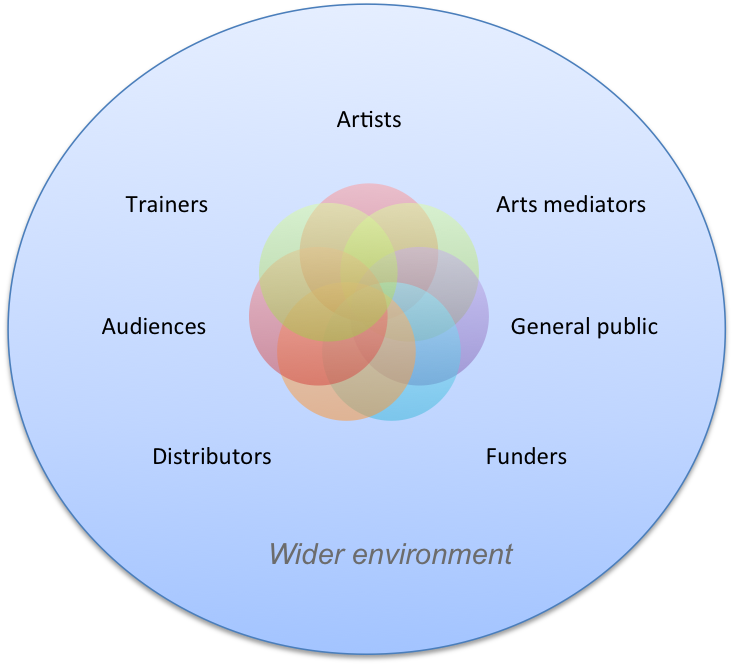

Tony Shannon, Acting Director of the Creative Industries Innovation Centre (CIIC) described some of the work they are doing for the Creative Industries (CI’s). According to Tony, all of the creative industries seem to struggle with a basic level of business-mindedness.

Tony urges creative businesses to make use of resources on the CIIC website (www.creativeinnovation.net.au) such as the Revenue Master. As simple – and he himself admits, simplistic - as the tool is, he says it is too often that he comes across creative businesses that have not done a basic revenue forecast of this nature.

Tony mentioned an analysis which I am currently working on with CIIC. We are looking at Centre’s findings across the hundreds of creative industry business reviews which the Centre has done over the last three years. The picture which is emerging is that creative businesses’ key challenges arise because of weaknesses in business fundamentals, such as strategic planning, sales, finance and systems and processes.

Whilst the study does not yet include the screen sectors, Tony and the audience speculated as to how much these attributes of the broader creative industries might apply to the screen industry.

For Love and Money – presented by Simon Molloy

Simon Molloy spoke on the topic of “Psychic Income”. Psychic income is the difference between what a producer does earn through their films, and what they could earn in an alternative profession.

In 2007, AFTRS surveyed 4,500 Australian producers. The survey found that Australian producers work for love and not money, sacrificing professional careers and tens of thousands of dollars in incomes in other fields to become screen producers. Drawing from and building upon results from the 2007 survey, Simon is investigating and attempting to be more precise about the reasons why Australian producers forego such large amounts of money.

Whilst Simon was reluctant to testify to the rigour of this research by conventional academic economic journal standards, he takes heart from the achievements of Daniel Kahneman, who was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics in 2002. A psychologist by training, Kahneman is recognized for his work in disproving the economic rationalist assumption that all people work in an economically rational self-interested manner.

For more information, see Urban Cinefile’s previous article on psychic income at http://www.urbancinefile.com.au/home/view.asp?a=18807&s=Features.

Insights into the changing roles of producers in the new Australian screen culture, presented by Professor Deb Verhoeven

To avoid what Deb, Chair of Media and Communication at Deakin University, self-deprecatingly described as “an incredibly boring talk about data”, she refocused her question to “How do you survive as a screen producer in a hostile IP environment?”

In a vein strikingly resonant with that of Professor Fraser earlier in the day, Deb argued that what matters in this new environment is the “interoperability of content with data.” This ‘interoperability’ has 3 layers:

- Copyright owners must align their content with archival facilities

- Copyright owners must align their content on a semantic level

- Sharing of data

Deb foresees the second layer as the most difficult. She says it will involve standardizing meanings, which will require an army of what is known in academic circles as ‘ontologists.’ The layperson would probably identify them as the humble librarian or “information manager”.

The upshot of the above she says, is that we should be thinking more about production workflows (e.g. AGILE production techniques, Just-in-time (JIT) film production etc) instead of just production or distribution.

Deb’s notion of “interoperability” predicts that the difficulty in Michael’s National Content Network (NCN) will likely be setting up definitions and standards. I asked Prof Fraser if he knew Deb’s talk was going to align with his work so neatly. He confessed he didn’t, but added wryly, “We nearly embraced after her talk.”

Panel Discussion: How can Australian screen businesses become more sustainable, profitable and long-lived?

The panel consisted of Sandra Levy, CEO, AFTRS, Brian Rosen, President, Screen Producers Association Australia (SPAA), Neil Peplow, Producer and Director of Screen Content at the AFTRS, Dr Chris Burton, UTS Business School, David Court, AFTRS Centre for Screen Business.

The usual questions populated this discussion, such as “What is the correct business model for screen content creators?”, “What will happen to the independent film?” (left unanswered), and “How do we lift the Australian screen industry out of being a cottage industry and what is the role of Government in this?”

On the correct business model for screen content creators, Brian Rosen ventured that television has it pretty much right, with pay TV operators like HBO branding high quality content, and broadcast television producing “event” television.

One upshot of this for the feature film industry, is that he suspects there is a gap emerging in the film market at the $20-25 million budget level. This is because Hollywood’s response to the paradigm shift occurring in media has been to make big “event” movies, with lots of CGI. It was not mentioned in the discussion, but there was a pre-World Wide Web precedent for this gap in the Working Title films (e.g. Four Weddings and a Funeral) and Merchant Ivory films of the 80’s and 90’s (e.g. A Room with a View). The success of these films probably prompted the studios to create spin-off specialty studios such as Rogue Pictures, Miramax (created by the Weinstein brothers, but later purchased and remodeled by one of the big studios), and Fox Searchlight.

With regards to the last question, on “How do we lift the Australian screen industry out of being a cottage industry, and what role does Government play in this?”, it was Brian Rosen again that ventured an answer. He argued that to create a viable screen industry like Hollywood, you have to look to what Hollywood has that attracts the best ideas from all over the world. His answer to that is i) capital and ii) infrastructure. Consequently, he says it would be better to invest the $42 billion being invested in the National Broadband Network (NBN) instead into film production in Australia. This would attract film productions from all over the world, and the rest would follow.

The main disagreement (and there were many) between the panellists and some audience members appeared to revolve around the “business-mindedness” or otherwise of screen practitioners. Leading the “for” camp was Sandra Levy, who claims that the producers she has seen in her career, both in television networks and as CEO of the AFTRS have always “been market savvy, known their audience and are highly entrepreneurial in getting their films to market.” This was a claim supported by David Court’s own view of his AFTRS students.

On the “against” camp, i.e. screen practitioners do not appear to be business-minded, was Tony Shannon and other members of the audience. Clearly, Tony Shannon’s experience of creative industry practitioners, as well as Simon Molloy’s presentation would appear to suggest there is some evidence for this position too.

One attendee commented after the event that one of the statements by the panelist Neil Peplow was telling of a non-commercial mentality typical amongst even successful film producers such as Neil. Neil was describing the ravaging effects of piracy on his film income. He said that his film, Waking Ned Devine, had been illegally downloaded hundreds of thousands of times. “If”, he speculated, “every one of those illegal downloads were to be charged 50 cents, I would nearly have made a profit on my film!” The suggestion was made by the attendee that if Neil were truly “business-minded”, he would have been seeking to make millions rather than just breaking even. If this assertion is correct (and let’s give Neil the benefit of the doubt here – he was speaking off the cuff and his statement could equally be interpreted as a keen desire to redeem money from an irredeemable situation), then it is a mentality that runs against the lessons from David Court’s paper that a good creative business should be prepared to “negotiate its terms of trade”.

Perhaps though, the two opposing opinions can be reconciled. My own penny’s worth (or sixpence, if I was feeling especially wealthy in Shakespeare’s time): most Australian screen practitioners make films for love and not money. It’s such hard work that your heart has to be in it. However, once they have made a film, they can and do work in entrepreneurial and business-savvy ways to bring their film to a paying audience.

Yen Yang - Principal, Creative Industries, BYP Group

The arts appear to involve what Abelson (1963) termed ‘hot cognition’.

The arts appear to involve what Abelson (1963) termed ‘hot cognition’.