This article gives you the details of my reasoning behind my predicted Apple Car.

The Thinking of Horace Dediu

The main analyst I refer to in this article is leading technology analyst, Horace Dediu. We cite materials predominantly from his two blogs and podcasts at Asymco (asymco.com) and Asymcar (asymcar.com). Dediu, a former student of ‘disruption theory’ pioneer Clayton Christensen[13], and now a director at the eponymous Christensen Institute, focuses his analysis upon disruption using Apple as a lens for study and comparison.

Although Dediu has made no firm statement upon the actual shape or functionality of the Apple Car itself, Dediu is on record as believing it will be influenced by certain key criteria. He looks particularly at Apple's past history and its key strategies that brought it success, as well as examining the history of the broader automotive industry itself to try to understand what these key criteria will be.

I go one step further and 'fill in the gaps' left by Dediu's criteria to give the reader a more tangible sense of the type of vehicle that Apple, or some other innovative companies, may seek to build if they were to start a car project from 'scratch' with a view to disrupting the incumbent automotive industry.

Apple’s track record in innovation – a late bloomer

From Apple, Dediu notes that what brings it success is not strictly 'disruption' in the sense defined by Clayton Christensen. Disruption theory predicts the disrupting company generally starts with a 'lower-end' product that initially appears so insignificant to the incumbents that it is ignored. Instead, Apple is rather distinctive in that it tends to make 'high-end' products. Nevertheless, it has been seen since its inception, making what was a previously 'low-end' product category, better designed and more usable, charging a premium for superior execution.

Apple even goes so far as to enter a product category somewhat after a segment has gained traction, but nevertheless succeeds way beyond these pioneers despite their ‘first-mover’ advantage, through superior execution.

These differences in approach are important in understanding how Apple may execute on a future product. Below are examples of ‘the Apple way’.

The iPod and iPhone

The iPod and iPhone are excellent cases in point. The iPod was a late entrant into the digital music player business. Regardless, they became the number one selling digital music player through superior execution. Their big innovation for that device was to develop the digital ‘scroll wheel’ to allow easier use. Additionally they changed the way music was sold through the introduction of the iTunes Store a few months after the iPod’s launch.

Similarly with the iPhone, smartphones had achieved some market success by the early 2000’s with comparably sized smartphones being produced by Palm and Blackberry. It wasn’t until 2007 that Apple entered the smartphone race against the firmly entrenched Blackberry.[14] Apple famously did away with the tiny physical keyboards on these devices that many people struggled to use, and improved the touch screen experience compared to what was used on the Palm devices. Once again, Apple took an already established segment, improved the interface and opened up the market for smartphones to even more people.

Apple’s DNA: A tradition since inception

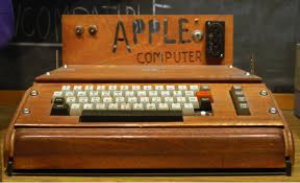

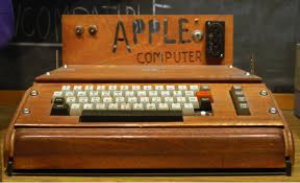

So much is apparent from Apple’s recent history, but many may not have been around for its early history. However a brief examination of this early history shows the ‘DNA’ of the company emerged very quickly even during its start-up years. For example, the first Apple computer delivered a superior package to the numerous other start-up personal computer makers around at the time in the 1970’s, offering as it did, the first personal computer with an easy to read output (a 'monitor' or TV screen rather than punch cards in binary), and an easy-to-use input device - a QWERTY keyboard, making it immediately recognisable to a population familiar with mechanical typewriters.[15] At the time, these additions were considered revolutionary in a personal computer.Image 5. The first personal computer, the Altair 8800. Note its difficult to understand output ‘display’ and lack of easy data input.

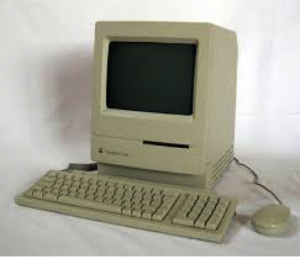

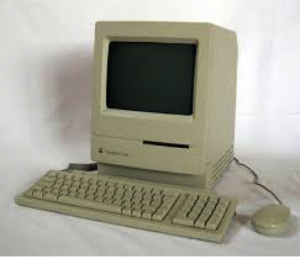

A few years later, Apple went a step further with the Macintosh making the user interface even more user-friendly by introducing the graphical user interface and mouse which were developed at Xerox PARC and essentially given to them by an executive at the then dominant Xerox corporation.[16] Clearly, that Xerox executive did not understand the value of his company's own research, but Jobs did, appreciating the ability of the technology to allow anyone to use a computer which had hitherto been amenable only through an inscrutable computer command line interface.[17]

In this way, we see Apple, time and again, introduce a new product, which despite its lack of primacy into its segment, still competes with non-consumption.[18] i.e. People who had never purchased these product categories before, would buy one when the Apple version came out.

In the case of the iPhone, it created a market so strong that Apple could weather the 2008-9 GFC, recording stunning growth during that period. By comparison, despite the far more benign conditions relative to the GFC, Apple CEO Tim Cook described the late 2015 quarter as 'the toughest he's seen for Apple' with their primary profit driver, the iPhone’s sales figures, receding in a year-on-year comparison. This reveals how much difference it is to compete in a rapidly saturating market, compared to the green fields of non-consumption.

Significant Contribution

The second factor Dediu refers to frequently is that Apple's track record and statements by its senior leadership strongly suggest that Apple would only enter into a new market, in this case, the car market, if it felt it could make a 'significant contribution'. Tim Cook’s statement, taken from before he became CEO, and in response to the inevitable analyst question regarding ‘What will Apple become without Steve Jobs?’ is worth quoting in full (My emphasis added):

“We believe that we are on the face of the earth to make great products and that’s not changing. We are constantly focusing on innovating. We believe in the simple not the complex. We believe that we need to own and control the primary technologies behind the products that we make, and participate only in markets where we can make a significant contribution. We believe in saying no to thousands of projects, so that we can really focus on the few that are truly important and meaningful to us. We believe in deep collaboration and cross-pollination of our groups, which allow us to innovate in a way that others cannot. And frankly, we don’t settle for anything less than excellence in every group in the company, and we have the self- honesty to admit when we’re wrong and the courage to change. And I think regardless of who is in what job those values are so embedded in this company that Apple will do extremely well.”

- Tim Cook fielding analyst questions during 2009 Q1 earnings call

In his podcast entitled 'Meaningful', Dediu is on record as saying he feels this would mean that Apple is intent upon making an 'iconic car', in the vein of the Volkswagen Beetle, the Ford Model T, the Fiat 500, the Citroen 2CV, and the (original) Mini. Considering the sales volumes of these cars, Dediu asserts that Apple intends to make a car that can sell in the millions, with a minimum goal of 1,000,000, although perhaps achieved over some years.

External criteria – Changing the Means of Production

The third important criteria in understanding what the Apple Car would need to be, comes from an external factor – the history of the car industry itself.

Dediu argues that in automotive history, great changes have always come with the advent of a new means of production. He points out the three big changes of production in automotive history each brought their respective proponents to primacy. For Ford, it was famously the assembly line for the Model T. Ford was later overshadowed by General Motors, through a production method that allowed different plants to focus upon different components e.g. Engine, chassis, body, so that greater specialisation, efficiencies and variety of products could be accommodated.[21] He believes this led to GM's ascendancy in the post-war period.[22] More recently, Toyota employed its now famous Just-in-time (JIT) methodology that reduced supply chain logistics costs and improved quality through reduced inventory, reduced error and improved response time from factory to the consumer and back again. Toyota became the number one carmaker in the World in 2012. Consequently, Dediu feels that for Apple to become a significant carmaker, it must look to challenge or change the existing means of production.

The high cost of traditional sheet metal car assembly

For Dediu, this is more than just a historical coincidence. He points to the present high cost of car manufacturing plants, which he argues, cost in the billions to create. Much of the tooling is expensive due to the stamped sheet metal process used by most mass-manufacturing carmakers today. Tesla Motors – a carmaker Dediu frequently argues is not truly ‘disruptive’ in the Christensen sense - was fortunate to be able to buy a disused Toyota plant in Fremont, California for a bargain price of $42 million, but it has spent millions in re-tooling it. [23] As an alternative, Dediu points to the 'iStream'[24] production method developed by F1 McLaren designer, Gordon Murray. Using the steel tubing and rapid turnaround methodologies of the race car industry, Murray claims he can cheaply make cars in smaller batches than present car manufacturing plants which are only viable after they make a few hundred thousand cars (assuming the cars sell!). Murray says iStream makes short production runs of 15-65000 vehicles feasible, and improves the customisability of these vehicles too. Through using a methodology like iStream, Dediu speculates this could save a new market entrant billions.

iStream – a good fit with disruption theory

It goes without saying that these vehicles can be structurally very strong and necessarily light,[25] fitting in with Dediu’s speculation on a small Apple Car. The weight reduction becomes important in later calculations required to make the Apple Car’s speed and dynamics viable for the ‘job-to-be-done’.[26] It also fits in with the overall disruption theory of developing a cheaper product segment that many in the incumbent industry would deride.

Potential ‘disruptors’

Classic disruption theory suggests an incumbent will tend to be disrupted from ‘below’, in a cheaper product category that the incumbents dismiss until it is too late. Below is a quick summary of these ‘lower’ product segments and their issues. Note their compatibility with the iStream production methodology and its inherent strengths:

- The bicycle – relatively hard to use (balance), unsafe relative to a car, uncomfortable, especially if the distance is far, the weather hot/inclement or the terrain difficult e.g. steep roads.

- The motorcycle – even harder to use (balance, operate, maneuver at low speeds), unsafe relative to a car (there are innumerable morbid jokes about motorcycles) and uncomfortable especially in inclement or hot weather. Safety gear is extremely uncomfortable in hot weather and riding is unsafe/uncomfortable in the rain.[27]

- The scooter – a slightly easier-to-use variant of the motorcycle but still requires balance and skill to use at low speed. It is frequently too slow for freeways unless you get an expensive scooter – which begins to cost as much as a second-hand car, defeating one of the prime objectives of scooter ownership - reducing expense.

- Electric bicycles – similar issues as with the bicycle, although they do increase comfort enough to make longer road trips viable to even people of low fitness levels. Nevertheless the other issues it shares with bikes prevent most people from trying these (lack of safety/comfort relative to a car). In time, I nevertheless predict we will see a lot more of these, and electrified ‘balance’ scooters/skateboards/hoverboards (etc.) being adopted.

- ‘Autocycles’[28] and other experimental motorized vehicles[29]. Segways – Though Autocycles are slightly more comfortable and (supposedly) safer due to many adopting an enclosed ‘car-like’ shell, the Cambrian explosion of variants all share in common a tendency to suffer from being more expensive than a small, economical conventional car, obviating one of their main objectives – reducing expense. Examples include the numerous examples we see on such ‘vlogs’ as Translogic (on autoblog.com), most of which are priced above US$15,000 due to the maker lacking economies of scale. In particular, the GM EN-V[30] and the EO smart connecting car 2[31] look close to the idea I am arriving at.

- Handicapped/Seniors electric cart – Every now and again, one sees a bold senior citizen driving their electric cart on a road, outside the confines of their retirement village, usually with a fluorescently coloured pennant to bring their vehicle in line with the higher eye-line of car and SUV drivers. Their lack of power means the speed differential between them and cars is vast, and increases the danger such that this type of usage is understandably not widespread as a transport solution beyond a few hundred metres from the driver’s residence, along a footpath. Also, their association with the elderly probably makes them ‘uncool’ in the eyes of many.

Presently, many in the car industry would not consider the above product categories as threats to the conventional 4-5 seater ‘cabin on four wheels’. However, when these lighter, smaller vehicles are considered in the context of the strong frames and advanced materials used in Formula 1 racing car design that are possible in the iStream production methodology, they can begin to overcome many of the issues these personal transport solutions have in becoming more mainstream. When combined with ‘smart’ technology e.g. to auto-balance, park and avoid collisions, they become a much more viable solution to a broader range of people. i.e. they become product categories that compete with non-consumption.

To add fuel to this speculation is the fact that Apple have been seen to add ‘vehicles’ to their list of company activities in Switzerland.

The paragraph added is reported by Swiss site ApfelBlog:[32]

“Vehicles; Apparatus for locomotion by land, air or water; electronic hardware components for motor vehicles, rail cars and locomotives, ships and aircraft; Anti-theft devices; Theft alarms for vehicles; Bicycles; Golf carts; Wheelchairs; Air pumps; Motorcycles; Aftermarket parts (after-market parts) and accessories for the aforesaid goods.”

Rail cars? Bicycles? Golf carts? Wheelchairs? Motorcycles? Perhaps these are just necessary inclusions in the ‘vehicle’ category in Switzerland, but it serves as a warning to not close off options. For my part, I suspect Apple will adopt a four wheel format but in a ‘micro’ size, slightly larger than the electric cart seen here.

A product that addresses the emerging markets

Another factor mentioned specifically by Dediu in the context of the Apple Car is the importance of the emerging markets to Apple’s revenues.[33] Tim Cook clearly sees the importance of Apple continuing its initial success in China, and achieving similar success in India.[34] Consequently, it stands to reason that whatever future products Apple comes up with, whether a car, or some other device, it must provide a solution to problems that are relevant in not only the established first world markets that Apple dominates, but also in these populous new emerging economies, especially the large cities of China, India, Brazil and Indonesia.

'Jobs to be done' Framework

Interestingly, Dediu does touch upon the above issue when he refers to Christensen’s ‘jobs-to-be-done’ framework.[35] We quote the principle from the Christensen Institute’s website: [36]

“Customers rarely make buying decisions around what the “average” customer in their category may do—but they often buy things because they find themselves with a problem they would like to solve. With an understanding of the “job” for which customers find themselves “hiring” a product or service, companies can more accurately develop and market products well-tailored to what customers are already trying to do.”

Taken in the context of cars, the fundamental job that many cars are trying to solve is to get the person from A to B, safely, comfortably, affordably and quickly. Many cars also try to address stylistic and ego issues as a job-to-be-done.[37] Dediu frequently uses the example of Tesla cars, which he feels people buy to look both cool and wealthy (without being ostentatiously wealthy), but also environmentally conscious – something that no other sports cars could do as well as Tesla Motors.

When we take the ‘jobs to be done’ framework in the context of the emerging markets, we see that they share the problem of many in the First World, only worse. They too have traffic jams – much worse than ours in fact in the big cities of China, India, Brazil and Indonesia - and they too will find it difficult to get parking at their destination. Consequently, if we can envisage an automotive solution that helps alleviate or solve these issues in both the First World and Emerging Markets contexts, then this is likely to be a space that Apple is trying to address as well.[38]

New Business Models – The real disruptors

Another point that Dediu raises frequently, though not so much in the car context, is that people frequently (mistakenly) believe the technology itself is the disruption. However, there are many instances when the technology has been around for years, but the disruption does not occur until the business models the technology(ies) enables begin to operate.

An interesting example in the transportation industry is that of Uber. Using a variant of social media software to solve an information problem (i.e. People wish to find a lift to their destination; Drivers wish to find passengers), Uber is taking over a large portion of the taxi industry’s traditional business.

We also saw with Apple that the iPod in and of itself was not what revolutionized the industry. It was the iPod in conjunction with the Apple iTunes Store. Where previously the recording industry sold most of its content on physical media such as CD’s, in retail stores, the iTunes allowed for easy and legitimate purchase of just a single track at a much lower price point.

Other factors e.g. Aggregation Theory & Modularity Theory

Of course, the above-mentioned factors are not the only factors that may impact upon the success or failure of an Apple Car. Other theories that are frequently described in the context of disruption Aggregation Theory[39] and Modularity Theory. I am not fully abreast of these theories and can only speculate upon how they might impact the automotive industry.

Modularity

Dediu has described his 'Law of conservation of modularity'[40], my loose understanding of which is that he postulates disruption may occur when some significant change has occurred to make a system modular. Modularity, he argues will push some facets of development and slow others depending upon which is the ‘inferior’ component. In the context of the automotive industry it appears he identifies high degrees of modularity, with specialist suppliers supplying most components of the car, such as suspension, transmission, tyre technology, entertainment systems, etc. With an electric drive train, even more can be outsourced and commoditised, as electric drive trains are far simpler than internal combustion engines.

In fact, we see a similar phenomenon in the bicycle industry with gears (Shimano), seats, brakes and electric motors coming from suppliers, with the big brands assembling these products and repackaging them under their own brand name. Consequently, it is easy to envisage a modular industry quickly developing around a small form-factor vehicle, perhaps using ‘off-the-shelf’ components that are slightly upscaled or specifically designed for the Apple Car (BTW: Another Apple hallmark as we saw in the case of Corning developing ‘Gorilla Glass’ for Apple’s iPhone).

Aggregation Theory

With ‘Aggregation Theory’, Thompson states:

“Looking forward, I believe that Aggregation Theory will be the proper framework to both understand opportunities for startups as well as threats for incumbents:

- What is the critical differentiator for incumbents, and can some aspect of that differentiator be digitized?

- If that differentiator is digitized, competition shifts to the user experience, which gives a significant advantage to new entrants built around the proper incentives

- Companies that win the user experience can generate a virtuous cycle where their ownership of consumers/users attracts suppliers which improves the user experience

The Uber and Airbnb examples are especially important: vacant rooms and taxis have not been digitized, but they have been disrupted. I suspect that nearly every industry will belatedly discover it has a critical function that can be digitized and commodified, precipitating this shift. The profound changes caused by the Internet are only just beginning; aggregation theory is the means.”

We have already seen Tesla Motors performing software upgrades automatically that boost performance and identify any issues with their vehicles in a much more efficient manner than is possible with earlier cars. It will be up to the Apple Car’s designers and others operating in this space to conceive of what these might be, or alternatively develop a car ecosystem that allows developers the opportunity to address them at some later date.

Summary

When one considers all of these points together, we arrive at:

- A small car, possibly a very small car that may even be in a product segment that many may presently deride (i.e. asymmetrical) e.g. Micro cars, autocycle, 'smart car', or even electric cart or golf cart.

- A product that can sell in the millions ('significant contribution'), and competes with non-consumption (innovative or makes the user interface so simple and the product so comfortable and desirable, many more people can use it than its predecessor.)

- As a consequence, it will probably seek to solve the problem of getting person X from A to B by focusing on the big issues at hand not solved well by the existing dominant paradigm of car formats or other modes of private transport e.g. Traffic (jams) for cars, safety (of motorcycles/scooters and bicycles), convenience (e.g closed in cabin again, though this time to shelter from rain, or eg. Easy to use/steer, even a child could drive one safely, so no balancing required, no instability at low speed, no complicated manual gearbox etc), parking (e.g. Through self-parking smarts) etc.

- In addition to this, there will be another vector, in technology, that should also be present that will allow further revolutionary changes to essentially the same form factor, e.g. The gradual improvement of driverless technology e.g. Automated pilot software, e.g. 'Linking' of compatible cars to form small convoys, more accurate mapping etc etc.

- Another important factor around the question of the 'job to be done' that it solves in a superior way to existing car form factors, is that it be as much a 'job to be done' in the more populous cities of the developing world and emerging economies of China and India as it is in the developed world cities of London, New York and San Francisco etc. We can easily see that traffic jams are generally worse in these poorer countries, and can get much bigger as they experience major net migration to the cities and increased car ownership despite little improvement in infrastructure. This again helps identify the 'job to be done' as that which we described above, as the problems of traffic and parking are only worse in the big cities of less developed emerging economies due to their generally having poorer infrastructure. We speculate that a car that can somehow more efficiently use road space will help in solving this job to be done, be it a smaller form factor (perhaps narrow enough to use two abreast in one conventional road lane width), or a method of 'linking' or convoying with other cars in some meaningful way that improves traffic flow safely.

- We must also consider the possibility that the Apple Car may not be owned like most traditional cars through a purchase, but through licensing, subscription or some other business model. We have already seen Apple’s buyback model deployed.[41] Perhaps they will take it one step further offering a yearly subscription model, displacing the phone retailers and telephony companies that presently bundle phones with phone and Internet contracts. How then might these new business models apply in the context of an Apple Car? What would an Apple Car subscription or its equivalent buy you? Use of an Apple Car for one year, after which the subscription must be renewed or the car returned? Membership of a convoying service that allows one to use transit lanes, or relieves the member from driving for some part of his/her journey? Parking in a highly compressed row of Apple Cars that can auto-park and auto-unpark?

Some rough physical parameters for the Apple Car

To help paint a picture of the specifications and performance of such a vehicle, I refer to the existing performance characteristics and specifications of existing electric vehicles and extrapolate and interpolate from there.

Electric Bicycles

Curb Weight: Around 50-80 pounds (23-36kg)[42] with the lower spectrum being a more expensive ‘lightweight’ bicycle and the higher end being designed with a more powerful (500W) motor and steel frame.

A typical budget electric bicycle would tend to have a 200-250W motor and should push an average adult male (80kg, giving a combined weight including the bike of about 110kg) at around 25kph on level terrain with a standard steel frame.

EO smart connecting car 2 (a small ‘concept’ car)

| Size: |

2.58 m x 1.57 m x 1.6 m; Or rather 1.81 m x 1.57 m x 2.25 m (The indication of the length of the vehicle depends on the type of tire / tyre section. The values have been recorded with tires of type 200/60 R 16 79V.) |

| Weight: |

750 kg |

| Power supply: |

54V – LiFePo4 battery |

| Speed: |

65 km/h (40 mph) |

| Actuation/ Engine: |

4 x 4kW wheelhub motors; 10 x longstroke-Lineardrive with 5000N 1 x Folding Servo |

| Sensors: |

Hall-effect as well as string potentiometer sensors for angle and length measurementStereo-Kameras at the front and at the back32-Line Lidar for 3D-scans of the environment6 ToF 3D cameras for near field overview |

| Communication: |

CAN-Bus RS232 RS485 LAN |

Tesla Model S[43] (a conventionally sized, luxury sports car with a powerful electric motor)

Curb Weight: 4647.3lb (2107.8kg or just a little over 2 tonnes)

Powertrain: 70kWh or 85kWh variant microprocessor controlled, lithium-ion batteries

Length: 196.0” (16.3 feet or almost 5m long)

Width: 86.2” (7.2 feet or around 2.2m wide)

We speculate that Apple would wish to have some more conventional performance specifications, that could propel the vehicle up to a speed of around 110km/h to cater to Western markets, but not much more as few roads allow speeds beyond this. Even those that do allow greater speeds generally allow traffic to go at 110km/h. Keeping the Apple Car’s top speed lower than most internal combustion engines are capable of would be in keeping with Apple’s tradition of not engaging in ‘spec wars’. From the outset, Apple has always eschewed striving to be the ‘most powerful’ or the ‘fastest’, but instead chose to reach only those performance benchmarks necessary to do the job.

Extrapolating and interpolating from the above, I conjecture that a vehicle weighing around 400-700kg (made possible by the use of light, strong materials, with lower bounds limited by the considerable weight of batteries, presumably placed in the ‘floor’ of the car)[44] would need motors totaling from 10-30kW (smaller motors could be placed at each wheel and co-ordinated using software) to propel it to speeds between 80-110km/h with a range in excess of 300km – more than adequate for most purposes, especially ‘short runs’ to the shop/public transport hub or keeping up with commuter traffic in emerging markets.

If Apple were to build a car about the size of the EO smart connecting car 2, then it may attempt to reduce weight by using lighter, but stronger materials as that employed in the iStream methodology. However, because it would have more powerful batteries, which are the components that weigh the most in these types of cars – c.f. the 2 tonne Tesla S) that give greater speed and range (250 miles+), the weight may stay the same at around 500-800kg.

Pricing

As stated before, Apple tend to adopt premium pricing within the product segment they operate in. If they were making a conventional car, we anticipate they would be selling cars priced in the range of the Tesla Model ‘S’, or US$70,000/AU$100,000. However, we do not believe Apple will produce a conventional car for the numerous reasons mentioned above. Instead, we are looking at something more like a highly specced electric cart or autocycle. As mentioned, autocycles frequently are priced at US$15,000+ due to their lack of economies of scale. With a production technique like iStream, we anticipate these prices could be reduced below US$10,000, even with deluxe materials such as a carbon fibre body due to economies of scale. One price range the Apple Car may be trying to gun for is the US$35,000 mark for enough Apple Cars to move 4-5 people. This price mark is what many in Western markets would call the higher end of the family sedan car prices (think the Honda Accord Euro, and Mazda 6) and is also the stated price of the highly anticipated Tesla Model III.[46] So should the Apple Car come in a single seat configuration only, then we would expect four of them to cost below US$40,000.

Conclusion

In the context of personal transportation, we can all foresee that one day people may not even own cars, and instead hail the all pervasive driverless Uber car or its equivalent. But in the meantime – most experts predict that eventuality is at least 10 years away - can Apple come up with a solution that will be needed or wanted by billions?

Perhaps from the above criteria, Apple can craft a high quality, personal transportation vehicle that is more economical than the traditional car, safer, more comfortable and quicker than car alternatives (e.g. motorcyles, electric carts), but above all solves the jobs to be done around transportation much better than the traditional motorcar.

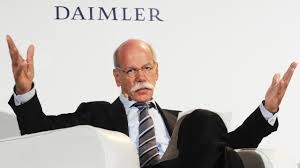

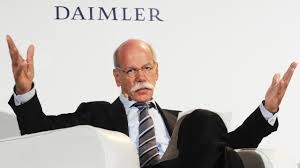

Doubt has been expressed by some as to this ever occurring. In February 2015 Daimler CEO, Dieter Zetsche stated:

“If there were a rumour that Mercedes or Daimler planned to start building smartphones then they (Apple) would not be sleepless at night. And the same applies to me".[47]

Then in late January, 2016, back from a recent tour to Silicon Valley, Zetsche acknowledged his surprise at the progress in Silicon Valley:[48]

“Our impression was that these companies can do more and know more than we had previously assumed. At the same time they have more respect for our achievements than we thought,”

Clearly, with Apple’s track record, no one should be dismissing the possibility of a successful Apple Car anymore.

Yen Yang is the Principal, Creative Industries for BYP Group.

To contact Yen, email yen at bypgroup dot com

- [13] Christensen is the pioneer of the seminal ‘The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail in which the author first popularized the term ‘disruption’ to describe the phenomenon of small start-ups displacing large, well-resourced incumbents: http://www.claytonchristensen.com/books/the-innovators-dilemma/

- [14] Blackberry phones were seen as so pervasive and addictive at that stage they were nicknamed ‘Crackberries’.

- [15] A wonderful account of these start-up years and the context of the making of the Apple 1 (as it is now known) is provided in Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak’s autobiography, ‘Woz’: Computer Geek to Cult Icon. http://www.amazon.com/iWoz-Computer-Invented-Personal-Co-Founded/dp/0393330435.

- [16] http://www.mac-history.net/computer-history/2012-03-22/apple-and-xerox-parc/2

- [17] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Command-line_interface

- [18] Here ‘non-consumption’ is used in the business sense. i.e. People did not buy computers prior to the Macintosh because they were too hard to use. When the Macintosh introduced a mouse and graphical interface more people began to buy computers: http://www.businessinnovationfactory.com/blog/2009/5/competing-against-non-consumption#.VsuWs87ZjAM

- [19] He also speculates it might be an autonomous ‘Winnebago’ in Asymcar 26: The iPod: http://www.asymcar.com/?p=509

- [20] Asymcar 27: Titanic: http://www.asymcar.com/?p=521

- [21] This was in contrast to Ford’s monotonous design made famous by a quote attributed to him: “You can have it (the Model T) in any color you want, so long as it’s black.”

- [22] Asymcar 24: Get rid of the Model T men: http://www.asymcar.com/?p=491

- [23] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tesla_Factory

- [24] http://www.istreamtechnology.co.uk/1/what_is_istream.html

- [25] http://www.istreamtechnology.co.uk/1/F1_for_you.html ; http://www.istreamtechnology.co.uk/1/Lightweight_is_good.html

- [26] I have only done rough calculations extrapolated and interpolated from existing vehicles, both on the market and in experimental form. These calculations are included below in the section entitled: ‘Some rough parameters’.

- [27] For those who have never worn full leathers and a helmet on a hot, humid Summer’s day, just take my word for it.

- [28] http://www.cheatsheet.com/automobiles/the-legacy-of-elio-and-why-defining-the-autocycle-is-important.html/?a=viewall

- [29] For an interesting selection of experimental vehicles, check out the Translogic vodcast on www.autoblog.com and https://drivingtothefuture.wordpress.com/ . Of particular interest to this author are the General Motors EN V (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=25J48arp3D4 ) and the EO smart connecting car 2.

- [30] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0tiHwzGsotA

- [31] http://robotik.dfki-bremen.de/en/research/robot-systems/eo-smart-connecting-3.html

- [32] http://apfelblog.ch/apple-marke-fahrzeuge/

- [33] Asymcar 25: The Selfie Experience: http://www.asymcar.com/?p=498

- [34] http://9to5mac.com/2016/02/04/tim-cook-india-iphone-apple-watch-android/

- [35] Asymcar 18: Cars of the People: http://www.asymcar.com/?paged=2

- [36] http://www.christenseninstitute.org/key-concepts/jobs-to-be-done/

- [37] This is also argued by Dediu to be a sign of the existing car format’s maturity and stagnation.

- [38] We can see an excerpt of Dediu’s thinking on one of his blog pages: http://www.asymcar.com/?p=21

- [39] A theory put forward by technology analyst, Ben Thompson on his Stratechery website: https://stratechery.com/2015/aggregation-theory/

- [40] http://www.asymco.com/2010/11/15/law-of-conservation-of-modularity/

- [41] http://www.apple.com/au/shop/browse/reuse_and_recycle

- [42] http://www.nycewheels.com/electric-bike-weight.html

- [43] https://www.teslamotors.com/support/model-s-specifications

- [44] Batteries in the floor of the car help provide a lower centre of gravity. They have been pioneered in cars like the Faraday Future and the Tesla Motors: http://www.roadandtrack.com/car-shows/news/a27797/faraday-future-concept-electric-car-ces-2016/ ; https://www.teslamotors.com/en_AU/modelx

- [45] http://blog.ted.com/test-driving-the-toyota-i-road-concept-car/

- [46] https://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/697678962588188672

- [47] Source: http://www.motoring.com.au/mercedes-benz-dont-build-an-icar-49356/ )

- [48] http://9to5mac.com/2016/01/25/daimler-ceo-apple-car-effort/